David has taught Honors Physics, AP Physics, IB Physics and general science courses. He has a Masters in Education, and a Bachelors in Physics.

Rotational Inertia: Physics Lab

Table of Contents

ShowRotational inertia, also known as moment of inertia, is the rotational equivalent of mass; a quantity that resists changes in the rotation of an object. Rotational motion is similar to linear motion. In linear motion, more massive objects resist changes in their velocity; in rotational motion, objects with more rotational inertia resist changes in their angular velocity. An object with more mass will have more rotational inertia, but the way the mass is distributed around the rotation point also has an effect on rotational inertia. If your mass is a long way away from the point of rotation, the object has more rotational inertia than if it is close by.

Today we're going to investigate rotational inertia and try to calculate a value of rotational inertia for a flywheel.

For this physics lab, you will need:

- A flywheel

- An axle for the flywheel

- A mount for the axle that will allow it to rotate

- A weight hanger

- Slotted weights

- A stop watch

- A meter ruler

- String

- Duct tape

- A protractor

Step 1: Assemble the equipment. The flywheel should be on the axle and the axle attached to its mount, allowing it to freely rotate. Put a piece of duct tape on the side of the flywheel so that you can more accurately see how it is spinning.

Step 2: Tie one end of a long piece of string to a stationary support near the axle, then wind the string around the axle until there is little free string remaining.

Step 3: Attach some weights to the weight hanger, and tie the other end of the string to the top of the hanger. The weight should be hanging not far below the axle.

Step 4: Measure the height of the hanging mass above the ground.

Step 5: Release the mass and let it fall under gravity. Start the stopwatch at the same time, and measure how long it takes to reach the ground. Repeat five times and note down your numbers.

Step 6: Calculate the average of your trials by adding up the numbers and dividing by five.

Step 7: Do another five trials, but this time focus on the flywheel. Use the piece of tape to measure how many times the wheel rotates during the motion. To make your number as accurate as possible, use the protractor to measure the starting and finishing positions. For example, perhaps your wheel rotated 6.25 times, because it rotated 6 full circles, and then finished 90 degrees beyond its starting position.

Step 8: Calculate the average of your trials by adding up the numbers and dividing by five.

Step 9: Use the ruler to measure the radius of the flywheel.

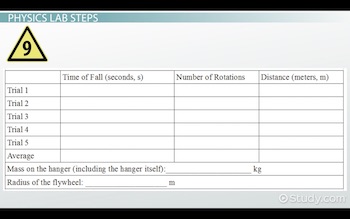

You can record your data in a table that looks something like this:

|

If you haven't already, now it's time to pause the video and get started. Good luck!

Now that you have your data, it's time to analyze it. In this motion, the gravitational potential energy of the mass is changed into kinetic energy. But because the mass is also turning the flywheel, some of the gravitational potential energy is instead turned into rotational energy. Therefore, we can say the gravitational potential energy in the mass at the start is equal to the kinetic energy in the mass right before it hits the ground plus the rotational energy in the flywheel right before it hits the ground.

So mgh equals 1/2-m-v-squared plus ½-I-omega-squared. Here, m is the hanging mass in kilograms, g is the acceleration due to gravity (which is 9.8 on Earth), h is the height the mass falls through in meters, v is the velocity of the mass before it hits the ground in meters per second, I is the rotational inertia of the flywheel in kilogram meters squared, which we're trying to find, and omega is the angular velocity of the flywheel in radians per second.

First of all, you can calculate v by taking the distance to the ground and dividing it by the average time it took to reach the ground and then multiplying it by two. The reason you have to multiply it by two is because the velocity of the mass when it reaches the floor will be approximately double the average velocity of the mass during the fall.

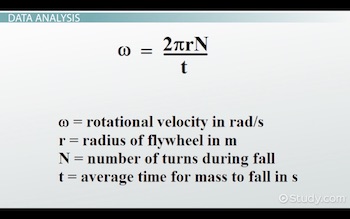

M is equal to the mass on the hanger you measured, g is 9.8, h is the distance to the ground, I is what we're trying to find, and omega you can calculate from this equation:

|

Omega is equal to 2 times pi, times the radius of the flywheel times the average number of rotations you measured divided by the average time it took for the mass to reach the floor. Plug all of these numbers into the equation, and solve for I to find the moment of inertia of the flywheel.

And that's it; you're done.

Rotational inertia, also known as moment of inertia, is the rotational equivalent of mass; a quantity that resists changes in the rotation of an object. Just as with linear motion, more massive objects resist changes in their velocity. In rotational motion, objects with more rotational inertia resist changes in their angular velocity. An object with more mass will have more rotational inertia, but the way the mass is distributed around the rotation point also has an effect on rotational inertia. If your mass is a long way away from the point of rotation, the object has more rotational inertia than if it is close by.

Using these concepts and an energy equation, we were able to investigate rotational inertia, calculating it for a flywheel.

Register to view this lesson

Unlock Your Education

Become a Study.com member and start learning now.

Become a MemberAlready a member? Log In

BackResources created by teachers for teachers

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.